Biënnale Gelderland 2022 – What About The Real Audience? (2022)

For Biënnale Gelderland 2022, curated by P1 Projects, SMET aims to unfold and propagate left-field knowledges, tirelessly and in huge numbers, populating the ‘public’, enabling other political imaginaries than the current neoliberal market ideology. From these imaginaries, refusals, and alternative utopias, communities can build/are already building different tools, as they seek to counter oppression in the wake of the struggle for the right to the city.

Nijmegen

Two impactful events in Nijmegen’s history are unlikely interlinked: The ‘friendly fire’ bombardment at the end of the Second World War, scarring the city, and the Pierson riots, the most violent squat-eviction in Dutch history. Nijmegen was facing a growing population parallel to a huge post-war housing shortage. The city’s priority was on (re)building new homes for its citizens, echoing national demands. The new city planning left a vacuum in the neighborhoods, around the city center like Bottendaal and Nijmegen Oost, exacerbating the scars. The dilapidation of these neighborhoods became a fertile ground for resident action committees and squatters by stopping its demolition and demanding better and safe homes. Nijmegen, next to Amsterdam became the capital squat city of The Netherlands. The current (continued) existence of a rich (cultural) network in Nijmegen is proof of this.

Squatting

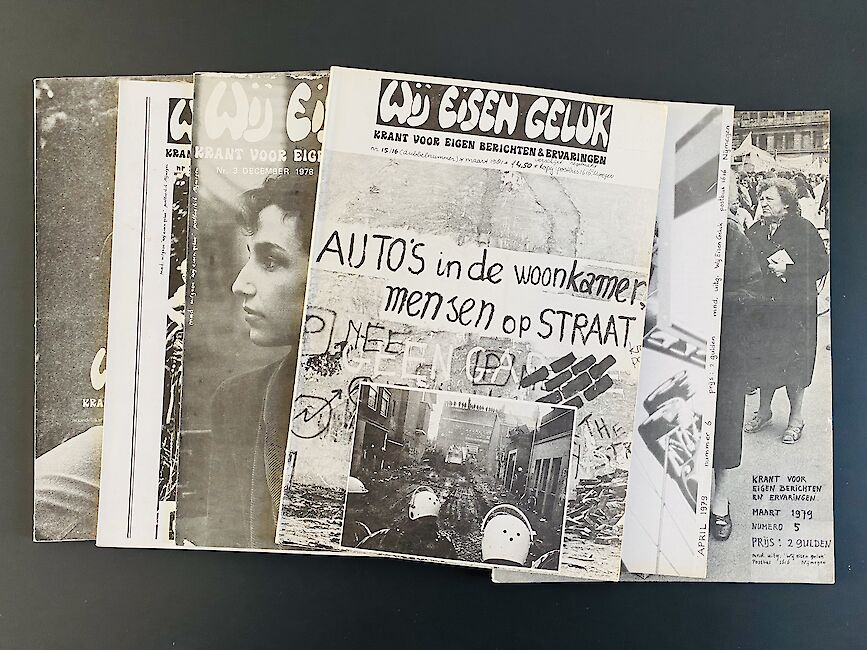

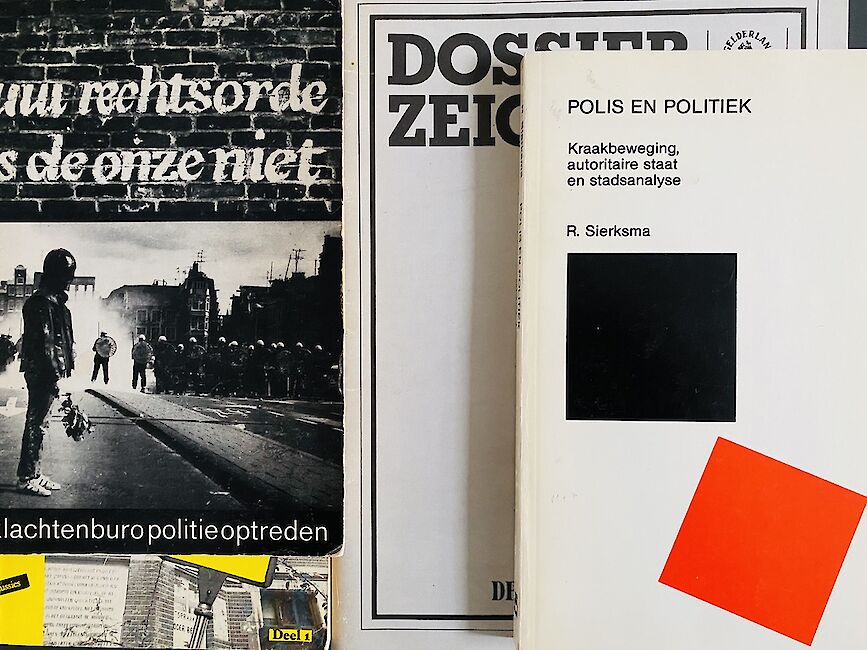

When researching Dutch public space, architecture, urbanization, and processes of gentrification it is hard to ignore the (historical) role of squatting. Its various movements appropriate space as both a self-signifier and a tactic to address the problems (and possible answers) of the housing crisis, skewed ownership structures, asymmetric urban renewal, and the commodification of public space. Squatters’ claims counter the exclusion of many social groups from the city’s urban core and provide them with non-commercial and self-managed services, dwellings, social encounters, and opportunities for political mobilization. This fundamentally engages Lefebvre’s concerns around the right to the city: the struggles to inhabit, appropriate, and recreate the city. These achievements of self-organization, appropriation and collectivity are an inspiration for generations to come, especially in times of hyper-individualism, diminished access to public space, and the continuing (artificial) housing shortage.

Activating the Archive

SMET does not limit their scope of research and intervention to the squatting movement, although it seems to have become a red thread within their body of work. Feminist herstories, African and Asian diasporic legacies, youth subcultures, and queer cultures are subjects of (embodied) interest, figuring in their contribution to the Biennale Gelderland 2022.

The Archive visually displays SMET’s research processes and results. SMET researched other ecologies of knowledge within the locality of Nijmegen and abroad. During their residency period, they have collected (hidden) (her)stories, culminating in a plurality of voices to be included in the archive. They take the archive as a collective, collaborative platform, one of many nodes and a place to facilitate encounters. Artists have been invited to activate the archive, intersecting it with their various practices, from performances to art publications, tattooing, graffiti murals, and video-and sound experiments. The archive is thus not seen as a static entity but a work in progress – open-ended.